Getting the most value out of playtests is a problem when designing a game. Here’s how the problem presents itself to me, and how I’m trying to deal with it.

Playtesting is a mixed pleasure for me. I mean, it’s a pleasure for sure – I love playing Close Encounters, and trying out cool stuff for it, so obviously I enjoy playtesting. But I also feel a lot of pressure to get the most value that I can out of each playtest session. There are several reasons for that – only having a limited pool of playtesters, not wanting to be “that guy” who demands everyone focus on their pet project, and so on – but it boils down to two things. I want to make the best game I can, and I can’t playtest as much as I’d like.

This pushes me into a conflict about how to maximise the value of my playtesting opportunities.

On the one hand, to maximise their value I need to be sure I’m getting reliable data from the playtests I run. That means I need to run as many tests as I can, so that I have more data-points to base my decisions on.

On the other hand, though, to maximise the value of playtests I need to have a big-picture view of how all the expansions interact. That means I need to test as much content as I can in each game, so that I can see how everything works (or doesn’t) in practice.

The gripping hand is that I can’t both run lots of tests and include lots of content in each test, because the more content that is included, the longer each game takes… and I only have a limited number of playtesting hours.

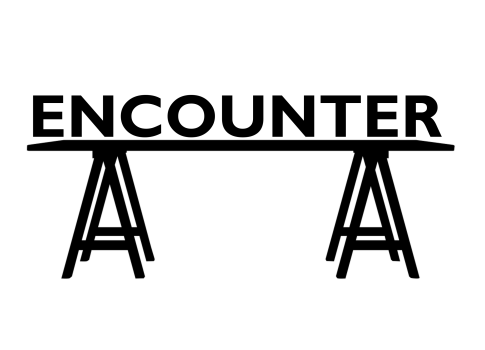

In my day-job, we would represent this conflict in a “conflict cloud”, like this:

You read it from left to right, first along the top (A-B-D) and then along the bottom (A-C-D`). Each arrow indicates necessity (in order to… I must…), and the lightning bolt shows the conflict between the two mutually exclusive actions I feel pressure to take (D and D`).

Being able to represent the conflict visually is useful, because it can help you find ways to break the conflict. We would start by writing down lists of all the assumptions we make about why each arrow link is true. For example, for the D-D` lightning bolt, part of the list might look like:

D-D’: I cannot both play more games and include more in each game, because…

- The more that is included, the longer each game takes

- I only have limited playtesting time

- The more that is included, the longer it takes to evaluate what to do with it in a playtest

- The more that is included, the higher the cognitive load on playtesters

- Playtesters have only limited cognitive capacity available

- Playtesters have only limited time available

- The higher the cognitive load, the slower each turn goes

We would try to get as many assumptions as possible, at least 20, and we would go for speed instead of focusing on accuracy. The point of this is to unleash your creativity, so it helps to have lots of things to play with!

Once we had the list we would then see what each item looked like if it was negated – that is, if it was not the case. Often this is as simple as adding the word ‘not’ to the assumption, or simply prefacing it with “I don’t need…”

The list from above would then look something like this:

The more that is included, the longer eachgame takesI can include more in each game without changing how long it takes- I do not only have limited playtesting time

The more that is included, the longer it takes to evaluate what to do with it in a playtestPlayers don’t need longer to evaluate what to do in a playtest, no matter how much is included- The more that is included,

the higherthe cognitive load on playtesters remains stable - Playtesters do not have only limited cognitive capacity available

- Playtesters do not have only limited time available

The higher the cognitive load, the slower each turn goesTurn speed remains stable, no matter the cognitive load

Doing this challenges the assumptions we’re making. Often, the challenge doesn’t help. For example, despite how much I would like it, my playtesting time is sadly going to remain limited! But sometimes it will trigger an idea about how to make it true. For example, look at the first point: I can include more in each game without changing how long it takes.

As it turns out, there is a way to make this true (at least partially). Some of my playtesters have quite a lot of experience with games of this type. Now, I still need the playtesters which don’t have much experience – there are more of them, and they can provide insights which the experienced ones are blind to. But the experienced ones can deal with more content without significantly changing how long the game takes. That means I can vary what I playtest depending on who is testing it.

With inexperienced playtesters, I can leave out most of the extra content and play lots of games. With experienced playtesters, I can throw most of it in and see how it all interacts. In other words, I can break the conflict simply by adjusting my playtesting parameters a bit.

The conflict cloud can help resolve all sorts of issues, not just those relating to business (or game testing!). If you want to know more about it, let me know either by message or in the comments. In the mean-time, I need to organise some more playtesting…